Dawn broke on Day 2 of Ramadan - actually it had yet to dawn, it was 4:21 a.m. - and Mr. Cat in Rabat & I were gently woken from our slumbers by the hyper-decibel eardrum-piercing strains of a muezzin urging all good Muslims in Rabat to haul their asses out of bed and pray. Being Ramadan, the volume of the speakers is adjusted from the normal "did I just hear something" range to a headache-inducing "omigod make it stop". Consequently, I (and most of my co-workers) are all tired and a tad cranky today. So because my brain resembles a jello fruit salad that has been run over repeatedly by a school bus, I am going to cheat a little. Cheating during Ramadan ... hee hee hee ... once an infidel, always an infidel.

At the behest of one of my readers (Cath: you can buy chocolate bars here called "Tink" - sorry, that 's an in-joke), I am reproducing in its entirety a

commentary by Rex Murphy from last week's Globe & Mail, Canada's national newspaper. I don't always agree with Rex and I don't always particularly like Rex, but I like to read Rex.

With no further ado, here's Rex....

Tolerance must flow two ways

It is not often that lectures on the finer points of theology and philosophy, delivered from so retired a venue as the University of Regensburg, turn the world, or at least a good part of it, on its ear. But it must be said as well that not every lecturer is the Bishop of Rome.

In Pope Benedict XIV's lecture, one that may be fairly characterized as both subtle and erudite, we have a talk whose explosiveness was almost entirely determined by a few words in it, and the fact it was the Pope who gave it.

Most of the Pope's address was a nuanced exploration of the relations between reason and faith. A good sense of the tone and nature of his talk, which is readily available in full on the Internet, may be taken from this sentence, which contains, as I see it, its central thesis: "Is the conviction that acting unreasonably contradicts God's nature merely a Greek idea, or is it always and intrinsically true?"

Hardly a red-flag item, even for the most excitable bull.

It was a few words of that address, which were cited by His Holiness to assist in the illustration of an elegant argument, a quotation from a 14th-century Byzantine emperor, that ignited, or at least has been the occasion for igniting, a great storm across parts of the Muslim world. The quotation and the words leading to it are these: ". . . he addresses his interlocutor with a startling brusqueness, a brusqueness which leaves us astounded, on the central question about the relationship between religion and violence in general, saying: 'Show me just what Mohammed brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached."

That one-sentence quotation of an ancient emperor, from an otherwise quiescent address, has set off a fury of anger and outrage. Churches were attacked in the West Bank, there have been demonstrations, and the Pope reviled as another Hitler or Mussolini.

Pope Benedict has invited Muslim envoys for talks, and has twice expressed his regret for the reaction to his lecture, but -- and this is not the same thing -- he has not apologized for his talk. Nor should he.

The fury in the Muslim world following the Pope's talk seems similar in two respects to the greater fury that followed the publication of those now famous Danish cartoons. The first similarity is that the volume and spread of outraged response gives every evidence of having been mobilized or concerted. That there is here, in other words, a "determination" to display outrage, less as evidence of profoundly wounded religious sensibility, than as political leverage against the West.

Not that I question some Muslims may well have taken deep offence in both instances, but that the offence taken has been magnified, and perhaps manipulated, for secondary motives.

The second point uniting these episodes, the point that I think the more consequential, is the expectation from some Muslim authorities that their sensibilities and beliefs are owed, as of right, a singular respect and immunity from all negative comment and remark. It is more than curious that those who don't believe in Islam should be expected to uphold the same codes of respect as those who do.

There attends this expectation, sometimes phrased as a demand, a further one: that should "offence" be taken, then whatever violence should ensue -- be it rioting, the burning of churches, or death threats -- must be laid at the door of the parties who "insult" Islam, not those who undertake violence in response.

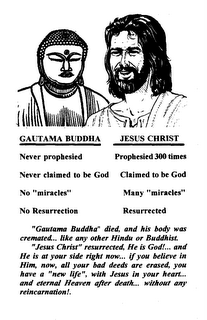

These considerations are troubling. First, because the respect and privilege claimed by some Muslims is not afforded religions other than their own in their societies. There is a magnificent mosque in Rome close to the Vatican. Do I need to say there is no basilica in Mecca? One religion should not claim rights it will not afford to all others. In too many Muslim countries, Christianity is institutionally -- and this is a kind word -- disadvantaged.

Secondly, the rhetorical violence visited on Christianity and Judaism ("apes," "pigs," "crusaders," "infidels") by various Muslim spokespeople is both fervid and frequent, and in some of its expression, utterly eclipses in its ferocity and deliberateness either the bywords of the Pope here, or the famous cartoons.

Tolerance, like its elder, respect, is very much an equal current that flows between two parties. I cannot see how burning churches -- as happened in the West Bank -- or crude attacks upon, and threats against, the Pope, provide a foundation to calls for "greater sensitivity toward Islam."

There are precious things in the West, too, two of which are freedom of speech and critical analysis. Storms of outrage, and almost predictable violence after every perceived slight, leaves me feeling that the cardinal values of the West will wait a long time for a portion of that respect that parts of the Muslim world insist upon, immediately and in full, as their due.

Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep. Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep at 2:21 a.m.. Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep by some moron banging a drum. Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep by some moron banging a drum incessantly. Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep by some moron banging a drum incessantly walking up and down the streets of your neighbourhood so that sometimes the sound begins to fade but then - oh! he's back! - it's louder than ever.

Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep. Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep at 2:21 a.m.. Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep by some moron banging a drum. Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep by some moron banging a drum incessantly. Imagine being jarred out of a deliciously deep sleep by some moron banging a drum incessantly walking up and down the streets of your neighbourhood so that sometimes the sound begins to fade but then - oh! he's back! - it's louder than ever.